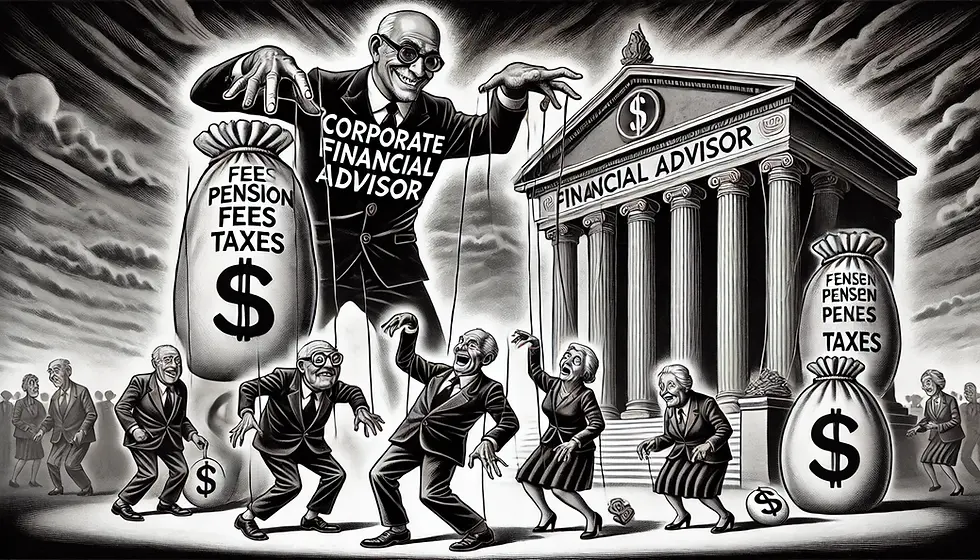

It is a curious phenomenon that financial planning, as it is so often peddled by the industry, begins and ends with pensions. The prevailing narrative is as predictable as it is myopic: squirrel away whatever pittance the system deigns to let you keep, entrust it to the labyrinthine machinations of the financial sector, and in return, after decades of toil, you may receive the privilege of eking out your final years in the modest comfort of subsistence. This, they assure you, is the pinnacle of prudence.

Yet, one cannot help but notice the conspicuous omissions in this supposedly holistic approach to financial wellbeing. It is not merely financial capital that one must consider, but human capital—the fundamental ability to earn, adapt, and sustain oneself. And beyond even this, there exist domains the industry has no interest in discussing: mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing. These, after all, cannot be neatly commodified into fee-generating products.

The evidence is there for all who care to read between the lines. Consider the recent report from recruitment consultancy Robert Walters, which states that over two-thirds of workers now expect to delay retirement due to financial necessity. A third of those who had supposedly ‘retired’ have since been compelled to unretire—some for financial reasons, others for their mental wellbeing. The narrative, of course, fixates upon pensions: high living costs, depleted savings, and the increasing necessity to prolong employment lest one’s retirement fund evaporate into an abyss of fees and inflation.

And yet, buried within this tale of financial woe is an unspoken truth. A full quarter of those returning to work did so not out of financial desperation, but for their own mental wellbeing. Herein lies the true revelation: the system has so successfully enshrined the pension as the sole arbiter of retirement that even the pursuit of purpose, social engagement, and mental stimulation is framed as an adjunct to economic necessity.

Chris Eldridge, CEO of Robert Walters UK, dutifully reinforces the orthodoxy: retirees return to work because they must, whether to prolong their meagre savings or to cushion the inexorable erosion of purchasing power. That some may choose to work for reasons unrelated to finances is, at best, an afterthought—certainly not something the financial industry wishes to examine too closely. The implication is clear: the moment you cease to be a contributor to the system, you become, in their eyes, economically irrelevant.

One might reasonably ask: is this truly the extent of financial planning? A grim equation of accumulation and decumulation, a delicate balancing act wherein the best-case scenario is dying just as your pension pot reaches its final dregs? Or could it be that true financial planning should consider the full spectrum of human experience? One’s ability to earn, to adapt, to cultivate a sense of purpose beyond mere economic servitude—these are elements of life that cannot be neatly distilled into an ISA or a pension drawdown strategy.

The financial industry, of course, remains silent on such matters, for it has no means of extracting its pound of flesh from your human capital, nor can it levy a management fee upon your emotional resilience. It would prefer that you see yourself as a mere financial instrument, an actuarial calculation, rather than a human being with agency beyond the sterile confines of a pension statement.

Perhaps it is time, then, to reconsider what financial planning ought to be. Not merely a means of passively accumulating financial capital to be siphoned off by the system, but an active, deliberate engagement with life in its totality. To plan one’s life first, and one’s money second. To prioritise not just the pension, but the person.

And that is something the system will never tell you—because, quite simply, it cannot profit from it.

Comments